S.S. AUSTRAL

SINKING IN SYDNEY HARBOUR, AUSTRALIA, 1882.

Subsequent raising and refitting to sail on until 1903.

Written from personal research by George W. Randall, co-founder in 1996 and former Vice-Chairman Kinloch Castle Friends' Association.

SINKING IN SYDNEY HARBOUR, AUSTRALIA, 1882.

Subsequent raising and refitting to sail on until 1903.

Written from personal research by George W. Randall, co-founder in 1996 and former Vice-Chairman Kinloch Castle Friends' Association.

|

While coaling in the early hours of 11 November 1882

(Photograph 23 from George Bullough's Photograph Album VII. Australia.)

|

*

but the newest

and finest vessel on the

England to Australia route when she arrived in Sydney on her maiden voyage on 30 June 1882.

England to Australia route when she arrived in Sydney on her maiden voyage on 30 June 1882.

Less than five

months later Austral was sitting on the bottom of the harbour

in

Sydney's Neutral Bay, off Circular Quay.

On 11 November 2024 it will be 142 years since the sinking.

Sydney's Neutral Bay, off Circular Quay.

On 11 November 2024 it will be 142 years since the sinking.

*

This

article brings together in one place personal research, publicly available material and

illustrations from dozens

of sites on Google concerning the life

history of the Orient Navigation Company’s Steam Ship Austral.

of sites on Google concerning the life

history of the Orient Navigation Company’s Steam Ship Austral.

A full list of sources is given at the end of this paper.

All are gratefully acknowledged!

********

A QUICK SUMMARY OF THE

In

September 1892, twenty-two year old George Bullough embarked

on a

thirty five month world tour.

On Sunday, 20 May 1893 he arrived in Sydney Australia on board the restored steamer

Austral which had sunk eleven years previously while coaling

in Sydney Harbour’s Neutral Bay with the loss of five lives.

Bullough returned home in August 1895,

when he immediately set off on an eight month “supplementary cruise”

aboard

his newly purchased steam yacht “Maria” which he renamed “Rhouma”.

******************************************************

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN ... ... ...

On 30 October 1894 Bullough arrived in Auckland the day SS Wairarapa hit rocks

close to Miner's Head, Great Barrier Island,

New Zealand, almost 128 years ago.

I have posted an article on this tragic event, the third worst in New Zealand maritime history.

It can be viewed by clicking on -

S.S. WAIRARAPA WRECKED MINER’S HEAD, GREAT BARRI...

close to Miner's Head, Great Barrier Island,

New Zealand, almost 128 years ago.

I have posted an article on this tragic event, the third worst in New Zealand maritime history.

It can be viewed by clicking on -

S.S. WAIRARAPA WRECKED MINER’S HEAD, GREAT BARRI...

******************************************************

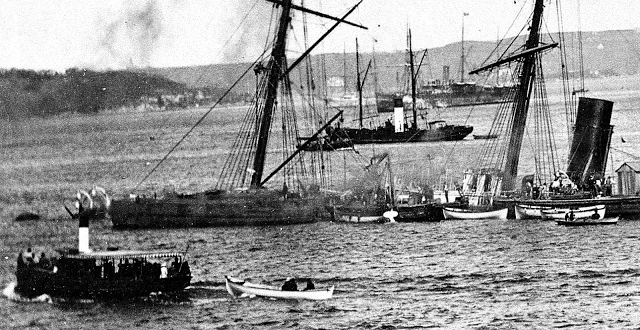

(Photograph 23 from George Bullough's Photograph Album VII. Australia.)

While coaling in the early hours of 11 November 1882

**** **** ****

After

discharging the passengers and cargo, coaling commenced for the return

journey, “this had barely

started when the ship developed a moderate list.”

This was

trimmed, but no one from Captain Murdoch down questioned

why a vessel designed

to carry 5,500 tons of cargo and coal should

exhibit clear evidence of

instability.

Built of mild

steel, the vessel was 474 feet long, 48 feet wide with a depth of 37 feet.

Austral had five

decks; a promenade deck capable of being used in all weathers; an upper deck of

steel covered with three inches of teak; the main deck also steel with three

inches of pitch-pine over; the lower deck of steel from the line of the engine

and boiler room casing out to the ship's side and covered with three inches of

pitch-pine; and the orlop deck of yellow pine 2½ inches thick.

Load line

displacement was 9,500 tons. Engines were 3

cylinder compound inverted.

|

| Full width Dining Saloon. |

Austral had

four boilers heated by six fires giving a steam pressure of

95-lbs, sq. inch.

“The (Admiralty) contract

stipulated 5,800 indicated horse power but on the delivery run the engines

developed 7,114 horse power and coal consumption was 1.3-lbs. per hour for every

horse power indicated,” but the ship was empty of passengers and cargo and

met no inclement conditions.

*

The single 22 foot diameter propeller was driven by a hollow shaft of compressed steel and comprised four blades of neutral manganese bronze, the boss being of cast steel.

The pitch of the screw was 30 feet.

The single 22 foot diameter propeller was driven by a hollow shaft of compressed steel and comprised four blades of neutral manganese bronze, the boss being of cast steel.

The pitch of the screw was 30 feet.

|

| Third Class passenger saloon. |

For the more technically minded, “the propelling machinery consisted of a compound

inverted cylinder surface condensing engine, having one high pressure cylinder

63 inches in diameter and two low pressure cylinders each 86 inches in diameter

with a stroke of five feet. Each cylinder was fitted with two equilibrium

piston slide valves in lieu of the ordinary flat valve slide valve.

Steam and

hydraulic gear were provided for reversing and handling the engines when

required.

Two surface condensers and pumps were placed at the back of the

engines, each low pressure engine being connected to its own condenser and air

pump.”

Austral’s Chief engineer was John McDougall.

*

The interior was “to the highest standard (with) massive

staircases of polished oak,

rich

decoration of white and gold and walnut paneling emblazoned with the coats

of

arms of England, other great nations and the British colonies.”

The owners “introduced several novelties for securing

increased comfort

and safety, including a hospital, well stocked library and a cabinet

organ

in the saloon where passengers reclined on velvet upholstered sofas,

or sat in revolving

chairs under a large

domed ceiling above magnificent painted glass panels.”

A corner of the Dining Saloon. (Illustrated London News)

Furnishings would be secured to the floor, dining chair seats would swivel on their legs.

*

The dining room was “said to be superior to those in the best Sydney hotels.”

Cabins for the time were well fitted, spacious and comfortable.

In an article on 21 March 1882 the Melbourne daily The Age wrote,

“the first-class baths are of marble and the lavatory accommodation

for all classes is unusually abundant,

even the third-class passengers have a bathroom specially reserved for them.”

“At night dynamo-electric machines generate electricity to light up the whole ship. Arc lights give a power of 3,600, and the Swan 3,400, or a total of 7,000 candles. The current was provided by two Siemens alternating current machines each driven by a separate engine strong enough to drive both.”

LEFT: Saloon passengers reclined on velvet upholstered sofas. RIGHT: Twin berth cabin.even the third-class passengers have a bathroom specially reserved for them.”

|

| ABOVE: Swan Ceiling Mount Obscure Globe.

(Electrical Times)

Swan Wall Mount Obscure Globe. |

| |

A gangway, four feet wide, ran right along Austral’s hull sides this permitted the staterooms to be constructed with windows instead of portholes and “the portholes to be opened even in rough weather without any fear

of water entering the cabin.”

(Quote and illustration: London News - Marine Engineer) *

|

(Illustrated London News)

|

Full width

Dining Saloon.

“The

commissariat department is well attended to, and the most hypercritical

passenger will have some difficulty finding any cause for complaint with fresh

meat, fish, butter and milk from the refrigerating chamber served with iced

wines, beer and mineral waters daily.”

(Picture and quote from: The Illustrated Naval

and Military Magazine.)

*

|

Austral’s four

masts and topsail yards were made of steel.

The upper topsail yards were

of wood and fitted with patent reefing gear and

so constructed they could be

lowered and stowed away along the sides of

the deck when the ship was steaming

against the wind.

The fore and main sails were square rigged, the mizzen and

jigger having fore

and aft sails, together Austral carried 28,000 square feet of canvas

which was

worked by steam winches.

Should steam failure occur the winches could be worked

manually.

|

| Oil painting of Austral under canvas by Thomas Goldsworth Dutton. |

Austral was principally powered by steam, her 2,500 ton coal bunkers being

filled through special coaling ports running amidships just below the main deck,

eight on the starboard side, seven on the port.

The coaling hatches measured 39 by 30 inches and when the ship was empty

of cargo were 54 inches above the waterline.

Coal consumption was estimated at 2½ tons per hour at average trial speed 17½ knots.

*

| |

*

Ahead of her time in many respects, the ship had a double

bottom, an inner skin and was divided into nineteen water-tight bulkheads, with

ten rising to the main deck; above which were

seven fireproof compartments. Should fire break out “the

ship is fitted with flooding-pipes from which large quantities of water or steam can be

forced” in all parts of the vessel.

Should flooding occur the pumps could handle 11,000

gallons a minute.

Austral was

also fitted with a 13,283 cubic foot freezer room, approximately 38 x 35 x 10 feet. The “refrigeration apparatus (was) of a new

plan and of such dimensions that 17,000 sheep (carcasses) could be carried

each voyage.” The equipment was the invention of forty-two year old Archibald Douglas Bryce-Douglas, head

of the engineering department of the ship’s builders, John Elder, & Co. “Most refrigeration hitherto used to add moisture to the air in the process of cooling,” Mr. Bryce-Douglas’s invention “not only extracts the heat, but expels the air drier than when it receives it.” “Air of an ordinary

summer temperature can quickly be reduced to 30 degrees below

zero.” During the delivery run “a temperature of ten degrees below zero was maintained in the empty chamber ... ... which is located just above the propeller shaft.” |

On the evening of 3 November, 1882, after a stormy and far from trouble

free second crossing lasting fifty-four days, Austral docked at Circular Quay,

Sydney. With her passengers ashore and most of her cargo unloaded, re-coaling commenced with a collier belonging to the Bulli Coal Company, pulling

along Austral’s starboard side and secured with hawsers.

(Austral’s port was alongside Circular Quay therefore only the starboard hatches

(State Library of New South Wales)

Arriving Sydney on Friday 3 November 1882 Austral

docked port side to Circular Quay

leaving only the starboard hatches accessible

for re-coaling.

After developing a slight list coaling stopped. This

was eventually trimmed and a week later the ship was moved to the Orient Line’s

mooring off Kirribilli Point.

In the interim William Cruikshank, Government Marine Surveyor,

inspected the troublesome engines and finding a flaw in the drive shaft

recommended it be removed for repair at workshops on nearby Cockatoo Island.

NOTE: The collier’s vertical mast can be seen to the

left of Austral’s foremast

which has a definite lean to starboard.

*

Inside the

ship’s bunkers, with all coal hatches open to aid

ventilation,

eighteen trimmers laboured to evenly distribute the coal as

it was loaded.

It was not only dirty but extremely dangerous work.

All

morning they swetted; when, with 230 tons loaded, Austral suddenly

gave a marked list to starboard and coaling stopped. Foreman William Hadden

sent for his supervisor, Carl Carlson, who found the starboard coaling ports

barely eighteen inches above the waterline.

Captain Murdoch

was consulted but refused a request by Carlson to carry coals

across the deck to the port side

in a bid to right the ship.

It took the crew of Woonona five

hours to put Austral back

on an even keel before

she could be moved. Warning number

two had come and gone with scant attention shown by those whose job it was to

ensure the safety of the ship and its crew.

Coaling was

stopped until Friday 10 November when Austral was moved from

Circular

Quay to the Orient Line’s mooring off Kirribilli Point, Neutral Bay,

a

distance of about one mile.

Meanwhile, Chief Government Marine Surveyor, William Douglass Cruikshank inspected the troublesome engines. During the outward voyage from England

the high pressure valve gear had twice

broken down necessitating disconnection,

the ship forced to proceed under sail assisted by

her two low

pressure engines. Mr. Cruikshank found “several minor faults

with (Austral’s) workings and a major flaw in the propeller shaft.”

(A marine

inspection was routine on all ships prior to maritime authorities issuing

the

necessary certificates enabling them to put to sea.)

At the

subsequent Inquest, Mr. Cruikshank deposed he had been

“called upon

to examine the machinery of the Austral on several occasions

since she arrived

this time. Last Wednesday, (8 November) I

suggested

that a length of the shafting should be removed from the tunnel.

It was the

length next to the engine. I had observed a flaw, hence my recommendation.

The length

weighed 10 or 12 tons. I did not consider removal of that weight from the

bottom of the ship would have affected her stability to the slightest degree.

When I examined the machinery I did not examine the valves and sea cocks.

When

I saw the vessel there was nothing in the defects of the machinery

which

rendered her un-seaworthy.”

The shaft,

technically called a “built shaft”, was made of “best steel”.

Mr. Cruikshank recommended

it removed for repair to nearby machine shops

on Cockatoo Island, about two

miles upstream.

This delay

was especially worrying as smallpox had broken out at Cape Town,

twenty-five

miles to the north. After three days, with repairs completed, Austral commenced

the last leg of her journey to Australia.

She soon steamed into “strong

westerly gales and huge seas” which for three days battered the vessel. One

thousand miles out from the Cape of Good Hope,

with the weather moderated, all

seemed “in capital order” until a problem

with the high-pressure piston again

required disconnection.

During the

eighteen hours for repair the canvas was unfurled and Austral

sailed

along at seven knots aided by her two low-pressure engines,

arriving Melbourne

on Wednesday, 1 November.

Despite assurances by the Pilot that the health risk

encountered at Simon's Town

did not require medical examination, immigration

officials insisted all on board

had to pass through the quarantine station.

Three days later Austral finally

berthed at Circular Quay,

Sydney, at the end

of her second voyage.

At 10 pm.

on Friday, 10 November, with fine, clear weather, no wind and the

sea dead calm,

coaling recommenced. In Austral’s bunkers the eighteen trimmers laboured to evenly

distribute the coal as it came down the chutes,

all starboard hatches were open to aid ventilation. After an hour, with thirty tons loaded, the slight list, resulting from the earlier coaling, had been corrected.

The open

ports, Foreman Hadden noted, were four feet above the waterline.

The Bulli Coal Company’s collier Woonona was contracted to coal Austral

The Bulli Coal Company’s collier Woonona was contracted to coal Austral

while she was berthed at Circular Quay.

Despite

the earlier listing occurrence, the master of the collier, Captain Morwick,

received no instruction to move his vessel to the other side of Austral.

Coaling continued at 25 to 30 tons an hour and by 2.30 am. the aft reserve

bunkers were full and loading moved to the mid bunker chutes.

Half-an-hour later Foreman Hadden again checked the height of the coaling

ports and found them to be “approximately two feet” above the waterline.

He also

noted “a slight list of the vessel to starboard ... not sufficient to excite

apprehension of danger,” he recalled at the subsequent inquiry.

Coaling

continued.

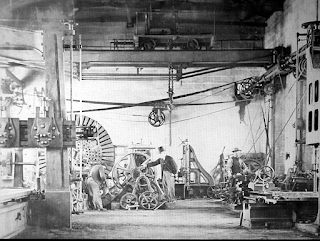

3.50 am. Saturday, 11 November, 1882.

As first light heralded the dawn of a new

day, the sound of rushing water drowned

out all other noise. Cries of “she’s

sinking!” were heard as panic broke out amongst

the trimmers as water poured in

through the loading hatches.

Lamp trimmer William Lowman, who had been assigned night

watchman,

went down to the saloon shouting “all hands on deck!” to rouse the

sleeping crew,

who because of the summer heat had opened many of the portholes

for air.

As Austral’s list increased it threatened to crush the collier tied alongside.

“Cut the ropes” cried Captain Morwick as Woonona’s engine was started and she slowly pulled away from the sinking ship suffering no more than a broken mast.

Austral's fore main deck was eighteen inches below the water at low tide.

The after part of the vessel was about ten feet under water

The after part of the vessel was about ten feet under water

inclined to starboard at 13 degrees.

>< * >< >< * ><>< * ><

Forty minutes

later, at 4.30am., with 1,500 tons of coal and 200 tons of iron on board, but short of several hundred tons of water ballast, Austral sank

stern first in fifty-two feet of water with a list to starboard of thirteen

degrees. No part of her hull was visible only the upper chart house on the

port side of the bridge, the four masts and two funnels. As it was less than

eleven months since Austral was launched and only her second

sailing, her owners had the ship insured for her actual cost £200,000.*

(*

Figure quoted at the subsequent official London Inquiry. Some newspapers report £250,000 as to Austral’s actual

cost.) |

Austral sank with a 13° list to starboard on a rising seabed of mud. View looking forward.

Note the water-tight bulkhead as integral part of the cofferdam.

Note the water-tight bulkhead as integral part of the cofferdam.

(From: The Engineer, Volume 35, Page 368 - 20 April 1883)

*

|

| The collier Woonona pulls away safely suffering only a broken mast. (Scientific American) |

Ali

Hassin aged twenty;

Saleh and Falim Mahomet

aged 23 and 25;

purser John

James Perkins aged 29 and refrigeration engineer, Thomas Alexander,

aged

twenty-two.

The Illustrated Sydney News reported all were interred at Haslam’s Creek Cemetery.

A

Coroner’s Inquiry convened on Monday, 13 November into the deaths of the five men. Over

six days the jury heard evidence from all members of Austral’s crew

and employees of the Bulli Coal Company. Possible causes of the accident

included the removal of the ten ton drive shaft, but the main focus was on the

amount of ballast water in the tanks directly above the keel.

On the night in question they contained only 180 tons, 22% of their 800 ton capacity.

On the night in question they contained only 180 tons, 22% of their 800 ton capacity.

Had this

altered the ship's equilibrium? Was the foreman of the collier guilty for not

moving his vessel to the other side when the list became evident?

+

Before the

jury retired to consider their verdict the Coroner, Mr. J. Shiell, J.P.

explained:

“a simple error of judgement would not render the captain or any of his officers liable to

a charge of manslaughter. However if the jury felt any person was guilty of

criminal negligence and this had caused the drowning of the five men, that

person or persons would be

guilty of manslaughter.”

The jury deliberated for five hours

before returning, the foreman announcing there was no chance of a unanimous

verdict. Would Mr. Justice Shiell accept a majority verdict? “No” was the reply.

After a

further ninety minutes deliberation the jury returned saying they had agreed

on

a verdict and found “the men drowned in the steamer Austral (as a result of)

gross negligence of Captain John Murdoch and officers of the ship.”

The

Coroner replied, “Then you find the captain and his officers ... guilty of

manslaughter?” Several jurors immediately replied: “No, we do not mean that at

all!” The Coroner said in that case they had not agreed on a verdict. He

reminded them that finding any of the officers guilty of gross negligence then

that constituted manslaughter.

The jury

retired again and four hours later returned naming the captain, chief officer,

chief engineer and carpenter as “committing a gross error of judgement.”

The

wording, substituting “judgement” for “negligence” ensured all those named

were

not guilty of manslaughter.

Captain Murdoch had his Master’s Certificate suspended.

Bow section during salvage work.

The Board of Trade in London held a formal investigation “into the

Bow section during salvage work.

With the Coroner’s Inquest concluded Captain Murdoch was petitioned to face a

Court of Marine Inquiry on 4 December in Sydney. With five days to the hearing

a letter from the Board of Trade in London was received

“requesting his Excellency the Governor (of New South Wales -

Lord Augustus William Frederick Spencer Loftus), to forgo the Inquiry.”

Justification for this unprecedented move being “the Inquiry should take place

in England where plans of the ship and evidence of certain scientific witnesses

could be taken into account.”

Despite the New South Wales’ Marine Board’s right to hold a hearing into the

sinking the Inquiry was cancelled.

Meanwhile local newspapers, particularly the Sydney Morning Herald,

disagreed. Citing the two previous occasions the vessel had clearly shown signs

of instability as evidence the captain and officers on board Austral did not

understand the conditions that affected their vessel.

That when deep in the water with cargo there was less need for ballast;

when the cargo was removed the need to increase ballast was essential to

maintain stability. The paper particularly highlighted that during the ship’s

maiden voyage Austral had developed a list when only 120 tons of coal had been

loaded for her return to England, and this in a 5,500 ton vessel!

The Board of Trade in London held a formal investigation “into the

circumstances attending the foundering of the steamship Austral in Neutral Bay, Sydney Harbour, on 11 November 1882, whereby five lives were lost" at Sessions House, Westminster, on 24 to 28 September and

1 to 3 and 6 October 1883, chaired by the Wreck Commissioner, H. C. Rothery.

The comprehensive and critical Report was published on 6 October 1883.

The Court concluded “that the ship foundered due to coaling having been continued

so long on the starboard side as to give the vessel a list sufficient to put the after port holes on that side under water, upon which the vessel filled and went down;

and that John Murdoch, the master,

and Godfrey Turner Richards, the chief officer, are to blame for the casualty,

but under (all) the circumstances it will not deal with their certificates.”

The full Board of Trade Wreck Report for Austral - 1883 can be found on Google:

The Report is comprehensive and well worth reading.

There is conjecture about the lack of stability testing prior to delivery and the

amount of water in the 800 ton ballast tanks at the time of the sinking

amount of water in the 800 ton ballast tanks at the time of the sinking

and why they were not full during re-coaling when the ship was “light”.

The ballast tanks were under the direct control of Captain Murdoch, Austral’s master.

* |

| There were no fatalities during the raising of Austral although diver George Murray was very lucky to be resuscitated after a screw in the pump to his airline became disconnected. |

Austral lay on a sloping muddy sea bed with a high risk of sinking ever deeper

and reaching a point beyond which raising her would be impossible.

With no time to lose the Orient Steam Navigation Company appointed engineers Stanford and Eldridge to proceed to Sydney to ascertain the best way to raise

their flagship liner.

Mr. George Eldridge, M.I.N.A., as the Orient Line's naval architect oversaw the whole plan in conjunction with Mr. G. Skelton Yuill, A.I.C.E., the Company’s resident Sydney manager at their 39 Pitt Street office, and Mr. John Standfield, M.Inst.C.E., for raising the ship.

On Saturday, 30 December 1882 Captain Chisholm, chief surveyor of the Surveying Department of Lloyd’s Association arrived in Sydney to represent the underwriters of the ship “and on their behalf, if necessary, to advise with regard to the plan to be adopted in raising her.”

Meanwhile sixteen divers had been busy working their way through the ship's dark interior salvaging movable and valuable articles from saloons and cabins. It was slow, dangerous work, their gear “weighed 150-lbs. when wet”, their air supply pumped through 180 feet of pipe.

Local boat

owners were quick to take advantage of interest the sinking generated.

Soon

regular excursions were leaving Circular Quay to give the paying public

a

closer look at the stricken vessel and efforts being undertaken to bring

her

back to the surface.

For

"6d. Return" one entrepreneur would transfer sightseers to the

steamer Alathea moored close to Austral for a

longer view of the salvage

work picking them up later.

RAISING OF

THE AUSTRAL

The new

steamers MASCOTTE and ELAINE leave No. 3 Jetty

every

fifteen minutes, from 6 to 6 during the day. No. 3 Jetty.

No. 3

Jetty. W. J. Harmer, Manager.

H.W.B.S.F.

Company.

*

THE

GREATEST NAUTICAL EVENT THE

WORLD HAS

EVER SEEN

THE

RAISING OF THE AUSTRAL

Steamers

will leave No. 3 Jetty through the day, and go round the Austral.

N.B. -

Note No. 3 Jetty.

No. 3 Jetty

*

RAISING

THE AUSTRAL - Steamers plying

from No. 4

Jetty every 15 minutes ONLY are allowed to

transship

passengers on board S. ALATHEA, especially moored off

Austral

for that purpose; return 6d. No. 4 Jetty only.

Another boatload of sightseers circle the stricken liner.

The white funneled vessel moored in the background is most likely the steamer

Another boatload of sightseers circle the stricken liner.

The white funneled vessel moored in the background is most likely the steamer

Alathea to which passengers could be transferred for a longer look at the recovery

work and be picked up later.

*

The initial method chosen to raise the ship was for divers to seal all open hatchways and ports, and pump the water out. Due to an “inadequacy of skilled divers” this proved impracticable so a heavily reinforced 410 foot long 30 foot deep coffer dam was constructed in weighted 16 foot sections and lowered in for assembly and “secured to the hull by bolts passed through scuttle lights and through oak toggles on the inside, and similarly to other toggles or stringers passing behind the stanchions on the promenade deck” by the divers. Made of four inch thick kauri pine planks strongly fitted together, the dam formed an encasing wall 10 inches thick rising out of the water well above deck level and heavily braced. It was made watertight by a covering of 26,000 square feet of canvas.

“The coffer dam itself was divided by a watertight bulkhead as the division gave great facilities in trimming the vessel as she rose.” |

The purpose of the coffer dam was to seal the ship, it did not encase the whole submerged vessel as in a floating dock. It extended over all port holes and loading doors - 410 feet of the vessels 470 foot length, and well above promenade deck height where it was secured with heavy timber bracing and steel hawsers.

Working day and night in shifts of six or eight hours, the divers were paid an average £1 for a six hour shift and thirty shillings (£1.50) for nine hours.

Labourers received one pound a week. It took sixteen divers and eighty-five men sixteen weeks

before the coffer dam was completed and tested.

On 26 February, 1883, everything was ready to remove over three million gallons of water weighing more than 11,500 tons.

|

The ship sank in 52 feet of water. The cofferdam

was constructed to withstand the lateral pressure

of 9-lbs. per square inch (almost 1,300-lbs. per square foot) the water outside

as the water in the vessel was pumped out.

of 9-lbs. per square inch (almost 1,300-lbs. per square foot) the water outside

as the water in the vessel was pumped out.

On Tuesday, 13

March 1883, 122 days after she sank and barely two weeks since pumping

began, Austral rose from the sea bed of Neutral Bay. With most of the

water pumped out it was now possible to inspect the interior of the ship. The Sydney

Morning Herald reported:

“The

first apartment entered from the promenade deck was the drawing room. The

walls, formerly of enamel and gold, the domed ceiling and windows ornamented

with graceful scroll work, the furniture cushioned with pale blue velvet, the

floor covered with thick Indian carpets and windows curtained with fabric of

white silk and gold thread, were now black and stained, the windows broken, the

curtains torn down and the velvet furniture and costly carpets rotted to ruin.

Passing down the massive staircase into the dining saloon, built to accommodate

120 diners, the same destruction was witnessed on a larger scale. Formerly the

ceilings of this magnificent room was decorated with white and gold, the end

walls ornamented with carved and emblazoned coats of arms of European nations

and British Colonies, the revolving chairs, cushioned with ruby velvet and the

saloon lighted by patent glass panels on each side, now the decorations are

obliterated, the velvet completely rotted and stripped off the chairs, the

coats of arms partly destroyed, the windows smashed and the handsome veneering

so saturated it strips off like paper. In the state rooms the same process of

destruction, everything not plain and solid, books wardrobes, settees, spring

mattresses, electric lamps, everything, all hopelessly ruined.”

*

As more

water was pumped out it became possible to see clearly the damage below deck.

“The scene of destruction is impossible to convey”, wrote a

reporter in The Sydney Mail, “the passages, cabins and floors are

covered in inches of black, slimy mud. The walls and ceilings blackened,

saturated with salt water and covered in marine growth. The stench of the bilge

water and the worst experience of all going through the storerooms with the

decayed and stinking supplies of flour, meat, tea, &c., which have been

soaking there for four months. Two of the men sent to clear the storeroom were

completely overpowered with fits of vomiting.”

Water had

initially poured in through the coaling hatches, then through the open

portholes, but once the deck was below sea level an appalling volume of water

surged down stairways and ventilator shafts, tearing doors off their hinges,

smashing walls, furniture, everything in its path; a massive tsunami sweeping

everything in its path in the confines of the ship.

Whilst the

open portholes had allowed water in they now provided a way out for crew members suddenly awakened from their slumbers.

*

*

|

| Workshops Cockatoo Island. |

"Unfortunately, a series of exceptionally low tides thwarted to slipping of the vessel and it became necessary to dock the ship each night

as it was too risky on account of the inside dimensions of the dry dock."

However, better news came when the engine room was examined.

However, better news came when the engine room was examined.

It was feared the engines and associated machinery would have been totally destroyed by the action of the sea water but this proved not to be the case. Following stripping down, a good clean and overhaul, most key parts were returned to working order.

Within twelve

weeks of entering dry dock newspapers reported Austral was cleaned

and repaired sufficiently to be returned for

refitting to her builders

at the Clydebank Shipyard of John

Elder & Co.

But first, on 28

May 1883, amid much fanfare a group of distinguished guests and those

associated

with the vessels reconditioning were invited for a trial run to test

the engines and handling

in preparation for departure to Scotland.

At 11.45am the

steamer Prince of Wales transferred 250 guests from Circular Quay

to the waiting Austral. Forty-five minutes later the tug Prince Alfred turned Austral’s

prow towards the open sea and she was underway.

Out of the harbour Austral turned right and set off down the coast gradually building up speed

while her guests dined and toasted the “success of the Orient Company.”

Captain Slader took his charge to almost 17 knots, informing journalists

he was going to sail her home to Great Britain via Cape Horn.

Out of the harbour Austral turned right and set off down the coast gradually building up speed

while her guests dined and toasted the “success of the Orient Company.”

Captain Slader took his charge to almost 17 knots, informing journalists

he was going to sail her home to Great Britain via Cape Horn.

Abreast of

Port Hacking Austral turned and made

her way back to harbour,

ending what was described “as a pleasant afternoon.”

|

The Maitland Mercury - 2 June 1883. Melbourne Argus - 29 May 1883.

Austral was

scheduled to leave Sydney under her own power on 5 June 1883 via Cape

Horn for Scotland under the command of Captain Henry Yorke Slader, R.N.R.,

she carried no passengers or cargo. Austral arrived

back in London on 3 August, fifty-nine days later.

Three days later

she sailed to her original builders at Glasgow and berthed into Queen's

Dock “to be refitted and redecorated in the same manner as before her

accident.”

At the same time

a series of stability tests were carried out. This involved moving a 10-ton

weight to various positions around the promenade deck and measuring the incline

of the hull.

At the London

Inquiry her designer, Mr. J. Shepherd, told the court he had neglected to carry

out any such test previously stating the builders were being pressed to deliver

the vessel and he “did not think, knowing the style of the ship that it was

necessary to do so,” adding, “he had designed the Orient (sister

ship to Austral)

and she was supposed to be the finest ship in the world.

Austral was intended to be an improvement having two feet more

beam.”

While anchored

in the River Clyde Austral was

rammed by the S.S. Cassia.

Incident Report from: Transactions of the Institution of Naval

Architects Volume XXVII:

*

SS Orient sister ship to SS Austral.

Built

1879 by John Elder & Co., Orient was the Orient Steam Navigation Company's first ship.

Single

screw, rigged for sail, speed 15 knots. 5,386 tons gross. 460 feet in length with a 46.3 foot beam and depth of 35 feet. Designed to carry 550 passengers. When

registered Orient was the largest ship in the world apart from Brunel's 19,000 ton Great Eastern.

Orient was scrapped in 1910 after

thirty-one years’ service.

(Photograph 22 from George Bullough's

Photograph Album VII. Australia.)

*

The stability tests

found that it was the deserted aft coaling ports that began to fill first.

The ship had in

fact been taking water for a considerable time before it was noticed by the men

coaling the forward ports. The examiners also found that if the whole of the

120 tons of coal had been loaded in pocket bunkers situated within 7 feet of

the side of the vessel this would explain how the accident happened. They

added “these valuable vessels should not be sent to sea till all the curves of

stability had been drawn, and measures taken to ascertain what cargoes they

were capable of carrying under varying conditions.” Despite this, the tests

found Austral “was

under almost every conceivable condition a very stable vessel.”

On 6 October the

investigating Court handed down its decision, stating the ship’s sinking was

caused be a series of small mistakes. “It was a mistake by the owners sending

the ship to sea without calculating her stability, and supplying the captain

with the information. It was a mistake to send her to sea with only four

certified officers. (The court recommended six.) It was a mistake of the

captain not to have taken warning from the previous lists, and to have turned

in without satisfying himself that the chief officer was vigilant and attentive

to his duties. It was a mistake of the chief officer to leave the ship in

charge of a watchman and turn in himself.”

Despite this the

court did not cancel or suspend either man’s ticket.

The total cost

of raising, cleaning and repairing the vessel, put at £50,000,

was defrayed by

the underwriters. >< + >< + >< +>< + >< + >< +>< + >< + >< +>< + >< + >< + ><

In April 1884, reconditioned to her former glory, Austral was

subjected to a series of sea trials before being chartered by the Anchor

Steamship Company for two voyages to New York from Liverpool prior to returning

to her Orient Line Australia route.

Returned to her owners, the Orient Line, Austral left

London on 21 November 1884 with 657 passengers bound for Sydney; forty-two days

later, 2 January 1885 she entered Sydney harbour. Only two of Austral's original crew, chief engineer John McDougall

and second officer Mr. O. Marshall, served on-board.

(La Trobe Picture Collection - State Library of Victoria.)

Fancy dress on board Austral.

*

The press

reported “the voyage throughout was rendered most enjoyable, concerts and other

entertainment, including a fancy dress being given. The latter proved a great

success all the ladies taking part and the handsome sum of 120 pounds being

realised for the different marine charities.”

Sadly during the

voyage three passengers died ... ...

Because of her unfortunate record maritime

superstition might have concluded

Austral was an unlucky ship, this was not the case. Apart from a brief spell requisitioned as a troopship during the Boer War Austral continued in service as a passenger /cargo liner for a further twenty years becoming a familiar and popular sight in Sydney Harbour.

On 5 January

1903 the pride of the Orient Line arrived in Sydney on her fifty-second voyage.

Twelve days

later she departed Circular Quay for the last time.

In May 1903 Austral left

London for the Italian port of Genoa to be broken up.

for a sum amounting

to between £13,000 and £14,000.”

The Sydney

Illustrated News commented:

“The sinking of

the magnificent Orient steamer Austral is an occurrence almost

without precedence in the annals of Maritime history.”

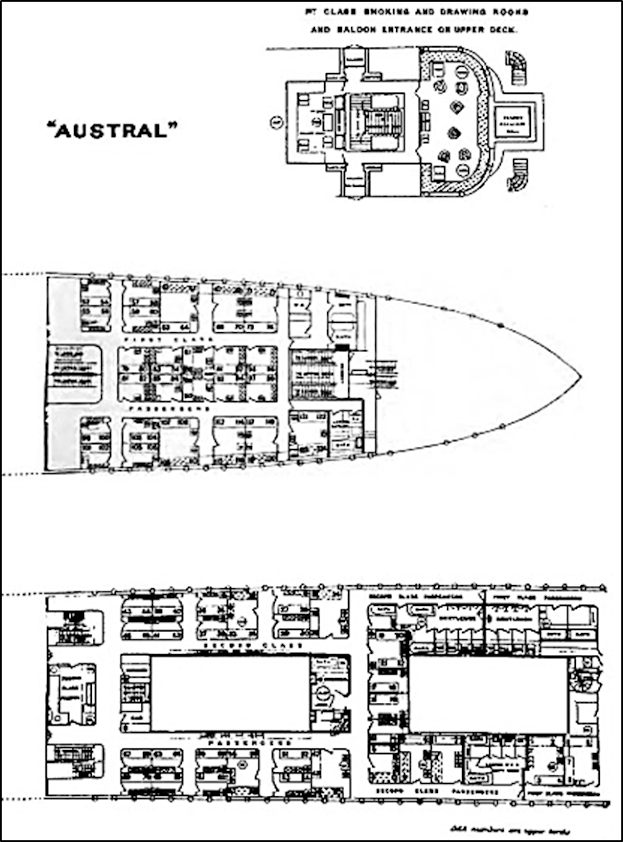

PLAN OF AUSTRAL FROM ORIENT LINE GUIDE 1888. Digitised from Google

*

Oil painting of Austral by Thomas Goldsworth Dutton

(c.1818-1891)

Dutton is recognised as the finest nineteenth century lithographer to record shipping and shipping scenes, he is also a noted water-colourist and oil painter.

Watercolour of Austral by William Lionel Wyllie - 1882 NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM GREENWICH *

This

article brings together in one place publicly available material and illustrations from dozens of sites by searching key words on Google. The text is the result of on-going research by the author stimulated by the

single photograph of SS Austral in the library at Kinloch Castle, Scotland, collected by George Bullough,

(later Sir George, Baronet), during his

world travels in the late 19th century.

The twenty volumes of over six hundred

pictures record events, places and people

from almost every continent, and all

have a story to tell.

The raising of the passenger / cargo

liner SS

Austral in

March 1883 from the seabed of Sydney harbour, the ship returning half way round the world via Cape Horn under her own power to her builders in Scotland for complete restoration, her return to service for another twenty years represents

Watercolour SS Austral by William Lionel Wyllie [1851-1931]

Painting of Austral by unknown artist.* (From: Modern Shipbuilding and the Men Engaged In It by David Pollock -Published 1884) << >> << >> << >> * << >> << >> << >> References: Scientific American Supplement - February 1883, June 1883 Money Market Review - April 1884 Illustrated Sydney News - 1883 Illustrated London News - 1882 The Illustrated Australian News - March 1883 The Marine Engineer – Jan. 1882, June 1882, Nov. 1882, Dec. 1882, May 1883, June 1903. The Sydney Morning Herald January, March and April 1883 The Engineer - April and October 1883 The Sydney Mail - November 1882 and February 1883 Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Raising the S.S. Austral 1883 United Kingdom Wreck Report for Austral Published 1883 The Melbourne Age November - 1882 Melbourne Argus - May 1883 The Mercury (Tasmania) - July 1882 The Daily Telegraph - March 1883 Remembering the Classic Liners of Yesteryear – www.ssmaritime.com Grey River Argus - 1883 Timaru Herald(New Zealand) - November 1882 Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute - Volume IX 1883 The Bendigo Advertiser - November 1882 The Granville Guardian - August 2010 Electrical Times Volume 1 - 1891 Orient Line Guide 1888 (Google) The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River Advertiser June - 1883 New Zealand Press (Issue 5353) - 1882 Taranaki Herald (New Zealand) - November 1882 The Inangahua Times - issue 1202, 1203 - December 1882 New Zealand Herald - November 1882, February 1883 Australian Government Archives The Bendigo Advertiser The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River Advertiser June - 1883 State Library of New South Wales George W. Randall Research Archive 1992-2017 The Wreck Report for SS Austral, 1883 - Port Cities Southampton The Press (New Zealand) - November 1882 Timaru Herald (New Zealand) November 1882 National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. (Watercolour) The Illustrated Naval and Military Magazine - Volume III 1885 Transactions of the Institution of Naval Architects - Volume XXVI 1885 Transactions of the Institution of Naval Architects - Volume XXVII 1886 The British Merchant Service Journal Volume IV - 1882 Photo SS Austral Allan C. Green - State Library of Victoria Ship of the Age - Austral - pages 46 - 59 Chris Frame Official - SS Austral Sinking Modern Shipbuilding and the Men Engaged In It (David Pollock) - Published 1884 La Trobe Picture Collection - State Library of Victoria Raising the SS Austral - Paper 1939 by John Standfield, M. Inst. C.E. All sources, without which this article would not have been possible, are hereby gratefully acknowledged. * REVIEWED WITH ADDED MATERIAL BY GEORGE W. RANDALL 13 FEBRUARY 2024 Text Copyright GEORGE W. RANDALL RESEARCH AND PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE |