C H I N A and J A P A N

1892-1895 GRAND WORLD TOUR OF GEORGE BULLOUGH

BACKGROUND INTRODUCTION:

BLOG 85 - ALBUM XVII * Photographs 1 - 19.

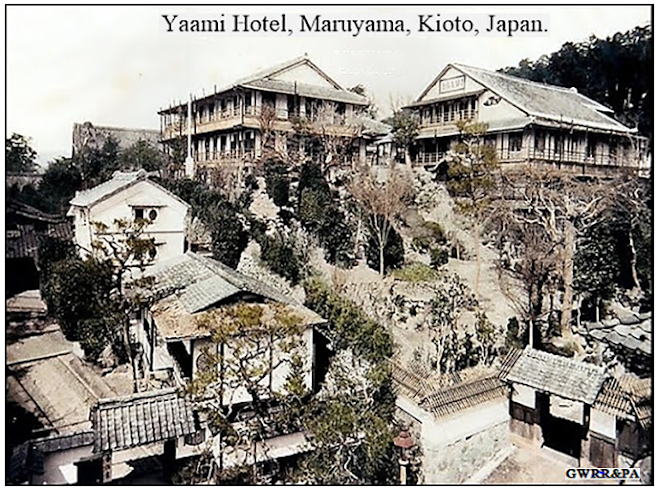

The original photograph attributed to Shanghai photographer William Saunders.

********** ALBUM VII - CHINA / JAPAN **********

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

***+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++**********+++++*****+++++*****+++++***

*****+++++*****+++++** * **+++++*****+++++*****

> + < > + <> + < > + <> + < > + <> + < > + <

*****+++++*****+++++** **+++++*****+++++*****

on the magnitude of the offence and period for which it had to be worn.

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

(H.M. Armed Cruiser)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

***+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++**********+++++*****+++++*****+++++***

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

CHINESE EXECUTIONS

Transcript of report in “San Francisco Call”

Volume 70,

Number 14 * 14 June 1891

Transcribed from the original

article in: “THE CHINA MAIL” -

Hong Kong 3 June 1891.

EXECUTIONS AT KOWLOON CITY.

The Manner in Which Fifteen

Chinese Pirates Were Beheaded.

“The Short but

Impressive Ceremony” as

Described by a

Paper Publisher in China –

A Tired

Executioner.

On the afternoon

of the 11th of May (1891)

fifteen prisoners were beheaded at Kowloon City. Among the number were six

Namoa pirates, including the three leaders of the gang, namely Fung San Yau,

Lai A Tsat and Chan A Yu. The other three were Wan A Fat, Cheung Sui Shang and

Ho Fat To. The last-named was the captain of one of the junks on board which

the pirates put plunder. The remainder of the fifteen were men sentenced for

various crimes, but they appear to have been all unknown in Hong Kong. The

execution attracted an unusually large crowd, and the interest of the

spectators seemed to centre in the Namoa men. This was particularly the case as

regards the large contingent of visitors from Hong Kong. It is just five months

and a day since the piracy of the (S.S.) Namoa and the murder of Captain Pocock

and Mr. Petersen took place. For a long time it seemed that the leaders of that

diabolical business were to escape with the fruits of their crime. They got,

thanks to the apathy of the naval authorities here, a very favourable start.

The police of the colony, if they were to depend on their efforts, were utterly

powerless, but the Chinese authorities bestirred themselves in the matter in a

way that showed they were very much in earnest. General Fong Ye, an officer of

untiring energy and unwavering determination, undertook the task of tracking

and bringing to justice those of the pirates who were known to have sought

refuge in Chinese territory. The result has exceeded in a very large measure

the expectations of the colony, for not only have fifteen of the miscreants now

paid for their crime with their lives but among these the three men who were

undoubtedly

THE LEADERS OF

THE GANG

have suffered.

One of these, Lai A Tsat - a man whose boldness and cunning in carrying out

such exploits have made him a terror both at sea and on shore for a long time –

was the person who had charge of that portion of the gang of pirates whose duty

it was to seize and keep guard over the European officers, engineers and

passengers of the Namoa. He was

referred to by the witnesses in the inquiry here as the pirate chief. The real

chief, however, was Fung San Yau. He was the man who directed the whole of the

operations, a man far superior to Lai A Tsat in intelligence, though not his

equal in daring. Mr. Wodehouse’s almost complimentary reference to Lai A Tsat’s

lack of brutality and bloodthirstiness was misplaced; for it is well known now

that this ruffian insisted on the necessity of setting fire to the ship before

leaving it, and Fung San Yau had great difficulty in overruling him. The other

leader, Chan A Yu, a Hakka from Shaukiwan, did not specially distinguish

himself in the piracy. He was under police supervision and on the eve of the

piracy sought permission from the Inspector of Police at Shaukiwan to go and

“collect some rents in the country.” Of the three remaining pirates whose

bodies are now lying on Kowloon beach, nothing particular is known here.

The short but impressive ceremony at the

execution was of the kind usual on such occasions. The prisoners were brought

down from Canton in a gun-boat, and amid the usual firing of guns from

war-vessels and fort, they were put into a couple of small boats to be taken

ashore.

TO THE EXECUTION

GROUND

Where a crowd of

Chinese and Europeans ranged themselves around an oblong square formed by armed

“braves.” The tide being out, the boats stuck in the mud when within about

fifty yards of the shore, and had to be shoved off and rowed to the pier.

A few minutes later the prisoners, with

their arms corded tightly behind them and their ankles loaded with chains, came

slowly along the rude pier to the place of execution guarded by a squad of

“braves.” Meanwhile the chief executioner and his two apprentices, having

cleared a space sufficiently large, and stuck four of their heavy swords into

the ground, whiled away the time in chaff with some of the officers present.

The Namoa men were among the first

lot of prisoners who arrived and a howl of execration from the crowd greeted

their appearance. “You’re Ko Lo Chai (Lai A Tsat),” said the chief executioner,

laying his hand on the shoulder of a tall, thin man with a “chop-dollar” face -

(a face deeply pitted with the scars of smallpox) - and keen piercing eyes.

“We’ll begin with you.” “All right,” responded the pirate leader, “I’m Number

One.” He had been swearing in English and Chinese, one of the Chinese officers

said, all the way to the execution ground. He was placed at one end of the

square and all the others knelt in a line with him. A few seconds sufficed to

put them in order, and then the slaughter began. Lai A Tsat kept looking around

at the executioner, while that worthy examined the sword which he had selected;

and while he held his long thin neck

outstretched he continued to speak, as if he wished the spectators to know he was not afraid.

“YOU MAY KILL ME

NOW,”

he said, “but

I’ll revive again,” on which Fung San Yau, who was the fourth man in the row,

muttered some comment. “Now, don’t you move,” said the executioner as he pulled

the pirate’s pigtail out of the way of the sword. The kneeling man said

something about each having his own luck, and as he said it the sword came down

and “Ko Lo Chai” was no more. The others, most of them very miserable looking

wretches, shuddered and gave what seemed to be an unwilling look round. They

had not long to wait, for the brawny butcher was getting through his work with

great celerity, prefacing each stroke with the warning. “Don’t move,” and

accompanying each blow with a vigorous utterance of a Chinese expression which

might be rendered into English as “Done for!” When he came to Fung San Yau it

was apparent to his experienced eye that that distinguished villain had

already, in a figurative sense, “lost his head.” The man of blood and steel

swore at him roundly and told him that if he did not keep steady it would be

the worse for him. It was the worse for him, for the blade struck him almost in

a line with the shoulders and the head did not come off, which was no doubt the

reason why there was a rapid convulsive movement of the legs for a few seconds

afterwards. The chief executioner, who found the others easier to deal with,

handed over the sword to his son, a promising youth of 15, at the twelfth man,

and he had no reason to find fault with the youngster’s work. When the end of

the line was reached the executioner in chief returned and completed the

decapitation of Fung San Yau. The whole affair only occupied a few

minutes. - China Mail. (Transcribed by George W. Randall)

Further reading: “Pirate Outrages: True Stories of Terror on

the China Seas”

by Douglas R. G. Sellick – Published 2012

NOTE: There is uncertainty as to the actual

date: 17 April or 11 May 1891.

Reviewing the numerous reports, particularly

referencing the photograph,

the latter date seems to be correct.

April 1891 predates George Bullough's World Tour by over eighteen months,

and his arriving in China by three years.

*

THE SEIZURE OF SS NAMOA BY PIRATES

*

THE SEIZURE OF SS NAMOA BY PIRATES

At noon on

Sunday the 3rd of December 1890 the SS Namoa, owned by Douglas, Lapraik & Company, commanded by forty-five

year old Captain Thomas Guy Pocock, departed Hong Kong on her regular twice a

week sailing to Swatow, Amoy and Foochow. On board were several Europeans and “more than 250 (other) passengers” including many Chinese from the province of Fuhkien returning to

their native homes after years of working in California “each with his little

hoard of hard-earned dollars, gained by frugal toil and self-denial in a

distant land.”

|

| SS Namoa |

From time to time a number of harmless looking Chinese passengers came up on deck and walked about in a seemingly aimless manner. A few days into

the voyage, with “thirty or forty” of the “harmless Chinese” strolling forward

and aft of the main deck, lolling near hatchways leading to the officer’s mess,

the ladder to the bridge, entrance to the engine room, and saloon doorways, the

signal was given take over the vessel. Each man “with a cutlass and two

revolvers in hand” had a role to play at his appointed station, for the attack

had been planned and carried out with much forethought. With the ship in the

hands of the pirates the course was changed to enable the vessel to “rendezvous

with their confederates, transfer their booty” to their three getaway sea-going junks.

Meanwhile the pirates ransacked the luggage and heartlessly robbed the returning labourers of

“their treasured packets of dollars”. In the process Captain Pocock and at least one passenger, a Mr. Petersen were killed. A Malay passenger was thrown overboard. Third officer Edie along with

other crew and passengers were injured. Before abandoning the Namoa there

was a heated debate amongst the pirates as whether or not to set fire to the ship. Amazingly and

fortunately, being unable to agree, the pirates departed.

After being “put

to rights” the vessel returned to Hong Kong where “public indignation was

great, and considerable pressure was brought to bear on the Chinese Government

to bring the pirates to justice … and make them pay the full penalty of their

dastardly deeds ... ... ...”

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

EXECUTION AT SHANGHAI (32)

Album XVII * Image 9 * Size: 10½ x 8¼ inches

Original photograph attributed to William Saunders, 1832-1892.

Owing to the limitations

of photography at the time, and to cater to an increasingly curious and

prurient interest in the West of Chinese life, this photograph is described as

being “staged.”

The kneeling victim,

stripped to the waist, head bowed, hands bound behind his back,

awaits the fall of the executioner’s sword, watched by a crowd of citizens, all of whom seem

to be looking at the camera. A high official seated on a grey pony oversees the proceedings.

awaits the fall of the executioner’s sword, watched by a crowd of citizens, all of whom seem

to be looking at the camera. A high official seated on a grey pony oversees the proceedings.

Album XVII * Oval image 10 * Size: 10 x 8½ inches

Original photograph attributed to William Saunders.

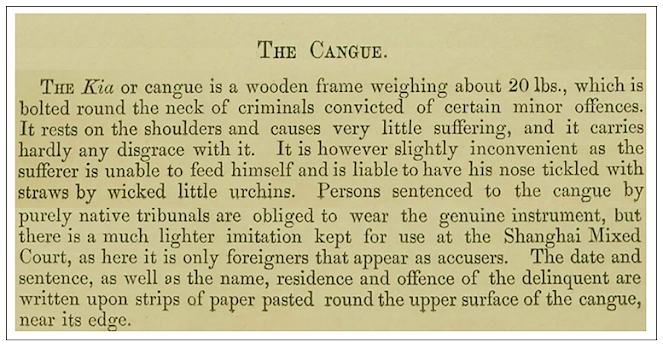

The Tcha or

Cangue consisted of two wooden sections enclosing the offender's neck and

locked, details of the crime being pasted on the front along with his or her

name.

The Cangue, derived from the Portuguese “canga”

meaning yoke,

on the magnitude of the offence and period for which it had to be worn.

Its size required the wearer to rely on

others for food and drink.

Unlike the English pillory or stocks it

was not fixed and had to be carried around

for the duration of the sentence, although in the picture above a chain around the

man's neck is secured to the ground.

for the duration of the sentence, although in the picture above a chain around the

man's neck is secured to the ground.

In this instance

the prisoner, led by the chain, has been taken by his guard to a place

where

he may be

fed by compassionate passers-by or friends. At the same time the prisoner

is exposed to

physical and verbal abuse, particularly by idle urchins who crowded the streets

in China as elsewhere always ready to insult the fallen.

The Great

Ming Legal Code published in 1397 specified the Cangue should be made

from seasoned

wood and weigh 25, 20 or 15 jin, roughly equivalent to 12½, 10 or

7½ kgs. (28, 22 or 17-lbs.) depending on the nature of the crime.

7½ kgs. (28, 22 or 17-lbs.) depending on the nature of the crime.

FORM OF PUNISHMENT

Album XVII * Oval image 10 * Full size: 10 x 8½ inches

Original photograph attributed to William Saunders.

*****+++++*****+++++** * **+++++*****+++++*****

MODES OF PUNISHMENT

Album XVII * Image 11 * Oval mounted on card overall size: 10½ x 8½ inches

Oval image: 7½ x 6 inches

Original photograph attributed to William Saunders c.1870

The Cangue came in many forms, all were designed to inflict pain and expose the

wearer to humiliation.

*****+++++*****+++++** * **+++++*****+++++*****

MODE OF PUNISHING PRISONERS

Album XVII * Image 12 * Detail from full size: 10½ x 8½ inches.

Original photograph and coloured version attributed to the studio of William Saunders.

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

|

| CHINESE STREET CARRIAGE

Album XVII *

Image 14 * Overall mounted size 10 x 8½ inches

Oval image 7½ x 6 inches |

Original

photograph attributed to William Saunders.

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

| COTTON WORKER (No. 33)

Album XVII * Image 15 * Size 10½ x 8½ inches

Original photograph attributed to William Saunders.BELOW: same image hand-coloured in William Saunders' Studio. |

COTTON WORKERS (No. 38)

Album XVII * Image 16 * Size 10½ x 8½ inches

Original photograph attributed to William Saunders.

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

Not identified.

Album XVII * Image 17 * Detail from full size 10½ x 8½ inches

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****+++++*****

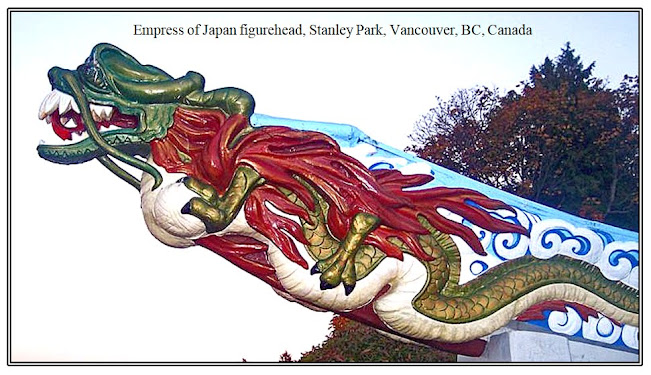

R.M.S. EMPRESS OF JAPAN(H.M. Armed Cruiser)

Album XVII * Image 19 * Detail from full size 10½ x 8½ inches

Embossed on photograph: (bottom left) SPYSIGHT * (bottom right) ELDAM IS ROTH

Launched in December 1892 by Lady Alice Maud Stanley, Countess of Derby,

RMS Empress of Japan was one of three sister ships, the others being Empress of India

and Empress of China, built by Naval

Construction & Armaments Co.,

(later part of Vickers Shipbuilding and Engineering) at Barrow-in-Furness,

England.

the 5,905 ton, twin-funneled ocean liner was owned by Canadian Pacific Railway,

her home port being Quebec City, Canada.

her home port being Quebec City, Canada.

465 feet in length, with a beam of 51 feet and draft of 35 feet, the clipper

bowed ship,

driven by reciprocating engines via twin propellers, giving an average

speed

of sixteen knots won her the Blue Riband for making the Trans-Pacific

crossing in 1897,

a record the Empress held for

twenty years.

Commissioned into the Royal Navy as an armed auxiliary cruiser in the

First World War

the ship became HMS Empress of Japan.

After the war the Empress returned

to her former trans-Pacific service to Yokohama in the

whole of which she made three

hundred and fifteen crossings, covering over two million nautical miles, during which she became known as “Queen of the Pacific”.

The Empress of Japan was scrapped in 1926.

Her original dragon figure head is preserved in the Vancouver Maritime Museum.

George W. Randall.

No comments:

Post a Comment