1892-1895 WORLD TOUR OF GEORGE BULLOUGH

|

| Jeweller’s Street |

each incorrectly depicting scenes in India as,

by inclusion, being in Singapore.

Photographs 23 and 25, (left), identified on the images

as “Jeweller’s Street” and “Manack Chouk”

over 2,500 miles to the north-west of Singapore.

|

| Manack Chouk |

and have been added to

|

EXECUTION OF RIOTERS, NEAR BATAVIA

Album XV * Image 18 * Size 11½ x 8½ inches PHOTOGRAPHEEN • VAN • NED • INDIE • BATAVIA - WOODBURY AND PAGE

Under Colonial Dutch guard convicted rioters, bearing placards describing their crime, queue as they await execution by hanging. circa 1880.

EXECUTION OF RIOTERS, NEAR BATAVIA Album XV * Image 18 * Detail from full Size 11½ x 8½ inches PHOTOGRAPHEEN • VAN • NED • INDIE • BATAVIA - WOODBURY AND PAGE |

******** ******** ******** ******** SINGAPORE

Singapore comprises one main island and

sixty-two islets off the Malay Peninsula separated by the Johor Strait. Following extensive land reclamation prior to and since independence in 1965 Singapore today covers an area of 279

square miles.

The population in 2018 was estimated at almost 5.6

million.

JOHNSTON’S PIER, SINGAPORE

Album XV * Image

19 * Size 11 x 8½ inches.

Original

photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore,

bearing oval embossed stamp in margin and number 4.

But Singapore's strategic position for sea trade meant bigger facilities were urgently needed. In 1864, following major land reclamation, a new quay designed specifically for loading and unloading ship borne cargo was completed along from Johnston's Pier. Built by convict labour on reclaimed land, it was named Collyer Quay after former Madras army engineer, Colonel George Chancellor Collyer, chief engineer of the Straits Settlements.

JOHNSTON’S PIER, SINGAPORE

Album

XV * Image 19 * Detail from full

size 11 x 8½ inches.

Original

photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore,

bearing

oval embossed stamp in margin and number 4.

THE PHOTOGRAPHER

– Gustav Richard Lambert emigrated from his home town

of Dresden,

Germany to Singapore in April 1875 aged twenty-nine, and established

his photographic studio at No. 1 High Street as G. R. Lambert and Co.

The new medium

of photography coupled with the huge increase in

tourism particularly from the west, made photographic prints increasingly popular.

Lambert's business quickly established a high reputation for artistic portraiture and landscapes, so much so that the firm became “leading photographic artists

(in) Singapore”

selling “over a quarter of a million postcards a year.”

Lambert

personally oversaw his business until 1885 when he returned to Europe

handing the

reigns over to his partner, Alexander Koch. For the next fifteen years

Koch established

new studios in Singapore; Medan and Deli on the island

of Sumatra, and

Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok, Siam.

Before the firm

wound up c.1914, G. R. Lambert & Co.,

were the largest

photographic business on the Malay Peninsula and official photographers by appointment

to King Chulalongkorn of Siam and Sir Abu Bakar, Sultan of Johor.

Reference: “A Vision of the Past:

A History of Early Photography in Singapore and Malaya – the Photographs of G.

R. Lambert & Co., 1880-1910” by John Falconer.

JOHNSTON’S PIER, SINGAPORE

Album XV * Image 19 * Detail from full size 11 x 8½ inches.

The Pier, affectionately known in Malay as Lampu Merah, “Red

Lamp” due to the red lanterns hanging at its farthest point to guide incoming

shipping, fulfilled this important task for seventy-eight

years until it was demolished in 1933.

A. L. Johnston

& Co., first proposed construction of a wooden jetty adjacent to their

seafront warehouses in March 1853 “for the convenience of the commercial and shipping

interests of Singapore.” Four months later, after consultation with the

government surveyor, construction

of a stone embankment with steps leading into the water was approved.

JOHNSTON’S PIER, SINGAPORE

Album XV * Image 19 * Detail from full size 11 x 8½ inches.

In early October 1853 Johnston’s again submitted plans for a jetty to the municipal committee, construction

being approved on the 19th of October subject to the cost not

exceeding 3,000 Singapore $ and a pier-keeper’s house be built at the land end.

The wooden jetty

was forty feet wide and 120 feet long and fitted with a crane,

it was to be

officially known as Johnston’s Pier.

A pier-keeper

was hired to maintain the crane and light the red lamps on the pier.

Over the years much

trade and visitors, including many royal personages landed at the pier. However it very soon became clear a pier built in the days of sail could no longer cope with ever bigger steam vessels carrying huge amounts of cargo

and visitors.

The pier was

demolished in June 1933 when Sir Cecil Clementi, 20th Governor of

the Straits Settlements, approved plans to build a new pier.

BORNEO WHARF - SINGAPORE

Album

XV * Image 20 * Size 11 x 8½ inches.

Original photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore bearing number 83.

With the opening of the Suez Canal, the advent of steam driven and ever bigger ships it soon became apparent the

original wooden wharves, transit sheds and warehouses built in 1856 had to be replaced

with much larger concrete structures to meet the rapidly growing sea trade.

The Tanjong Pagar Dock Company, registered in 1864 with capital of S$300,000, commenced trading in 1866 with a mere 750 feet of wharf space almost doubling to 1,440 feet by the end of the year. In the early 1870's telegraph links were established with Madras, India and onward to Europe and to Australia and Hong Kong. 1874 steam powered cranes and winches were introduced tripling unloading capacity and dramatically increasing coal bunkering, previously done by hand. Two years later the 450 foot long, 65 foot wide, 20 foot deep Victoria dry dock was constructed and in 1879 Albert dry dock, 496 feet long by 59 feet wide with a depth of 21 feet was opened by Sir Archibald Anson, R.A., K.C.M.G., Administrator for the Government. Through a combination of leases and purchases, by 1885, Tanjong Pagar operated two dry docks and 6,600 feet of wharves including Borneo Wharf purchased that year. In 1897 electricity reached the docks immediately doubling working hours. Refrigeration followed ... ports had to stay abreast of a rapidly changing world ... the height of the Victorian Era ... ... ... See Volumes I and II

Vast coal yards

- coaling stations - were required as steamships rapidly replaced sail.

From

the mid-1800's increasing numbers of trading vessels and British navy ships

ran on coal. In

the last quarter of the 19th century over half the world’s

merchant

shipping flew the Red Ensign.

In order to

protect and meet the needs of both its commercial and naval fleets Britain established

fourteen key coaling stations around the world where steamships could not only be provided

with coal but also food and water. Singapore, Hong Kong, Trincomalee and Colombo (Ceylon

today Sri Lanka) and the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius to name some in the Far

East were crucial to “an Empire on which the sun never sets.”

Aden at the

mouth of the Red Sea along with Simon’s Bay and Table Bay, South Africa,

were also

vital victualing ports particularly for the Australia and New Zealand routes, as Great

Britain ruled the waves at the height of Queen Victoria’s Empire.

VIEW SHOWING ENTRANCE. FROM SINGAPORE.

Album XV * Image

21 * Size 10 x 7½ inches.

The latter half

of the 19th century was one of unprecedented invention.

Steam

power, possibly more than anything else, was rapidly changing the world.

However,

it was fine to be able to move goods ever faster by sea, but what happened

then? Up

to the invention of the steam locomotive on rails the fastest people had ever

travelled on land was by

horse, with loads transported on wagons drawn by horses and oxen.

The

urgent need to modernise harbour facilities world-wide was made even more so by the

rapid laying of a rail infrastructure allowing faster distribution.

The chain of distribution was as strong as its weakest link. Harnessing the power of steam and the laying of railways were amongst if not the most important products of the Industrial Revolution, allowing the rapid transport of people and goods on a scale previously unimaginable.

Speed

of land and sea transport allowed perishable goods, particularly food, to be

brought to

market for the first time creating new business opportunity as shops

temptingly displayed

their wares to a curious and increasingly more prosperous public. |

******** ******** ******** ********

Original photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore bearing number 86.

Original photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore bearing number 86.

|

| HMS DIDO. (British Maritime Museum) |

(later Admiral of the Fleet),

became commanding

734 ton, 120 foot long corvette

HMS Dido, complement 145,

armed with eighteen

32-lb. guns.

Posted to the East Indies and China Station Keppel played a major part in clearing the area of pirates and, from 1839-1842, operations

during the First Opium War.

was renamed Keppel Harbour and the deep

water anchorage, Keppel Channel by

Acting Governor, Sir James Alexander Swettenham, in honour of Henry Keppel

who, as a retired ninety-two year old Admiral, was visiting Singapore.

At the same time, New Harbour Road was renamed Keppel Road, which “reportedly pleased Admiral Keppel very much.”

******** ******** ******** ******** ********

LEFT: A fishing village on Pulo Brani. RIGHT: Pulo Brani separated from Singapore Island by Keppel Harbour.

|

MALAY VILLAGE - PULO BRANI

Album XV * Image

24 * Detail from full size 11 x 8 inches

Original photograph by G. R.

Lambert, & Co., Singapore, bearing number 24.

See also Volumes I and II

|

|

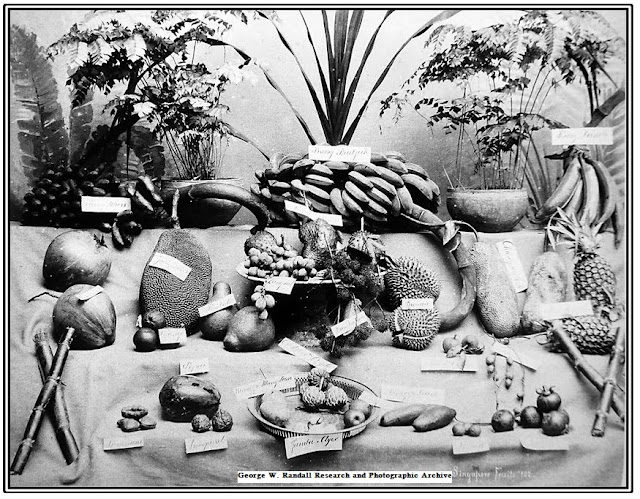

| SINGAPORE FRUITS Album XV * Image 26 * Size 9½ x 7½ inches. |

|

SINGAPORE FRUITS

Album XV * Image 27 * Size 11½ x 8½ inches.

Inscription: “B F K Rives” inverted and embossed along bottom edge of photograph. |

|

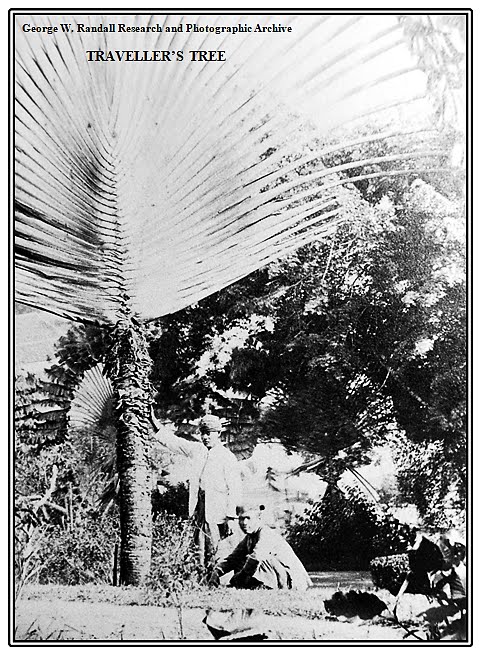

TRAVELLER’S TREE

Album XV * Image 28 * Detail from full size 11 x 8½ inches. |

******** ******** ******** ******** ******** ******** ******** ********

|

CAVENAGH BRIDGE - SINGAPORE

Album XV * Image 29 * Size 11 x 8½ inches

Original photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore, bearing number “10”.

The bridge was named after Major General Sir William Orfeur Cavenagh, last appointed Governor of the Straits Settlements from 1859 -1867 whose coat of Arms can be seen atop the cross-beams at both ends of the bridge. |

G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore, bearing number “10”.

|

| GENERAL POST OFFICE AND EXCHANGE BUILDING - SINGAPORE

Album XV * Image 30 * Size 11 x 8 inches

Original photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore, bearing number “213”.

|

|

GENERAL POST OFFICE AND EXCHANGE BUILDING - SINGAPORE

Album XV * Image 30 * Detail from full size 11 x 8 inches

Original photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore, bearing number “213”.

Tiffin (snack / light meal and

Billiard Rooms. with below to left: The Motion - Photographer and

Optician.

The Tan Kim Seng Fountain.

The fountain was

built to commemorate prominent Chinese merchant, businessman,

philanthropist and Justice of the Peace, Tan Kim Seng, (1806-1864), who, in 1857, donated S$130,000 to the Singapore Government for the construction of the country’s first reservoir and waterworks.

Originally sited in the cities Fullerton Square, it was unveiled on

the 19th of May 1882.

Album

XV * Image 30 * Detail from full size 11 x 8

inches.

...........................................................................................................................Original photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore, bearing number “213”.

Depicted in its original location the Tan Kim Seng Fountain is adorned with cupids,

the four Muses and faces of the god of the sea, Poseidon – who spent most of his time

in his watery domain - celebrating the newfound abundance of freshwater.

Designed by Derby, England, iron founders

Andrew Handyside and Company, (founded 1848), the Victorian-style iron fountain has three tiers and is decorated with classical figures.

Image: Choo Yut Shing

The lower bowl depicts

the Greek goddesses

of science, literature and the arts, “each bearing an object of her patronage … Calliope, the Muse of Epic Poetry, carries a writing tablet; Clio, the Muse of History, carries a scroll; Erato, the Muse of Lyric Poetry, carries a lyre; and Melpomene, the Muse of Tragedy, carries a wreath. Beneath the sculptures of the Muses are four faces of Poseidon, the God of the Sea …. each spouting water.” The fountain was relocated to Battery Road in 1905 and, in 1929, following land reclamation in 1922, to Esplanade Park where it can be seen today along Queen Elizabeth Walk, so named to mark the coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II on the 2nd of June 1953.

Restored in 1994

it was declared a National Monument of Singapore in 2010.

|

*************************************************************

|

VIEW OF THE HARBOUR - SINGAPORE

Album XV * Image 31 * Size 11 x 8½ inches.

Original photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore bearing number 187.

|

|

| VIEW OF THE HARBOUR - SINGAPORE

Album XV * Image 31 * Detail from full size 11 x 8½ inches.

Original photograph by G. R. Lambert, & Co., Singapore bearing number 187.

|

*************************************************************

PROBABLY

the term 'botanical garden' brings to the minds of most people something in the

style of a cemetery with a few trees and a great many oblong beds of herbaceous

plants, each bed with a white label suggesting a small gravestone. In a

properly appointed botanical garden most people expect to see also some hot

houses for orchids and a tank with warmed water for tropical water lilies and

lotus.

Should

an ordinary mortal, or even a botanist, be dropped from a balloon into the

middle of the garden at Buitenzorg, he would, for a time, hardly appreciate

that he was in a botanical garden. The usual 'ear marks' of such an institution

are certainly not apparent at first glance. The plants are mostly trees, no

warm tanks are necessary, and there are cool houses instead of hot houses. The

botanist, in looking at the names of trees would only now and then recognize

one he had run across somewhere in a text-book. Were it not for a very few

names, he might believe he had landed on some other planet. Certain it is he

would see few plants he had known before in the temperate zone.

After

a time spent at Buitenzorg the term 'plant' no longer suggests a small green

creature with pretty flowers—something which dies down in autumn and comes up

at Easter time. The plants at Buitenzorg are trees, and there are hundreds,

nay, thousands, of these; while only a trifling space is allotted to puny

little herbs—the things that we of the temperate regions know as 'plants.'

Of course the well informed naturalist knows the tropical world as the 'mother of life' and he expects to see a wealth of green, abundance of plant individuals and plant species. Still I doubt if anyone who has not actually visited a wet tropical region can have a very clear idea of the real luxuriance of Buitenzorg. In an ordinary temperate forest the number of species of trees can almost be counted on the fingers of two hands; the species in a northern coniferous forest might be counted on the fingers of a single hand. In a west Java forest there may easily be fifty species of trees within a distance of as many feet from an observer. In the whole island of Java there are probably a thousand different kinds of arborescent plants—perhaps more.

In the botanical garden an attempt is made to assemble the various plants of the Dutch East Indies and also to get the more notable species from other lands. This garden should be especially useful at this time to American botanists who may be intending to work in the Philippines. Java belongs to the same floral region as the American East Indies and our islands will doubtless show some likenesses and differences in flora, which will be of great interest. At Buitenzorg the visiting botanist has before him, in well organized form, an epitome of all tropical botany.

Aside

from any special interest which American botanists might have in Buitenzorg,

there are countless objects of general botanical interest to be seen there. One

who keeps in touch with modern botanical literature cannot but be struck with

the fact that in these days tropical botany is becoming more and more

important. The ordinary text-books still illustrate most points in physiology

and morphology by reference to plants of the temperate zone, yet there is an

increasing tendency to refer more often to tropical plants. The modern botanist

needs to know something of the tropics—the more the better. At Buitenzorg he

can learn a great deal in a short time.

The visitor,

ongoing through the gate of the garden, enters at once a long avenue planted

with canary trees (Canarium commune). Here is something with no

counterpart anywhere else in the world. As one walks down Canary Avenue in

early morning he notices perhaps, first the darkness, then looking up he sees

the branches above, overarched, as it were, to form the vaulted roof of a

Gothic cathedral. Here and there a few stray sunbeams, stealing through, make

bright patches of light on the moist roadway; the lianas, climbing up the great

tree trunks, are covered with dew and their huge leaves glisten as they are

gently waved by the morning breeze. Their long, aerial roots sway to and fro as

slow-moving pendulums. The great buttressed roots

of the canary trees, covered with epiphytic ferns and orchids, seem almost too

picturesque to be quite natural. Everywhere the eye feasts on a wealth of

green. It is hard to escape the thought that this is fairy land.

When

the visitor passes onward to the lake and looks across at the wooded island

where are planted magnificent flowering trees, shrubs of wonderful foliage,

and, more striking than all else, the red stemmed 'sealing wax palm'—when he

looks across the lotus and Victoria regia to all this tropical

luxuriance he must perforce become enthusiastic, even though he be by nature

the most cold-blooded of men.

The

garden has an extent of about one hundred and fifty acres. Through one end of

it passes the Tjilwong River and along here is some low ground, while further

back is higher land with more undulating surface, where, from certain vantage

points, good views may be had of the neighboring mountains. Only a few avenues

are open to carriages, but there are many neatly paved foot-paths usually

following a somewhat winding course. These foot-paths form the boundaries of

the different sections in which are trees of the various plant families

arranged in systematic and orderly fashion. To a botanist, interested in a

given group of plants, this is a most useful arrangement. It is much better

than the more common plan of grouping trees according to the kind of soil in

which they do best, and still better than the even more usual plan of

scattering them about, hit or miss, wherever there happens to be room.

A

visitor to the garden who is not a botanist will be disappointed that the

labels give only the scientific names of trees. He who may wish to see teak, satin-wood, ebony, the

mango, nutmeg, rambutan and

other notable trees must first find out for each the two many-syllabled Latin

words which are used to designate a plant for scientific purposes. As these

words are painted on the labels in a sort of modified German script they are

not quickly read. Besides this the labels are narrow and frequently the name

will not go in one line, but must be divided. The division is often made, not

with regard to the nature of the word, but to the convenience of the native who

does the painting. So one may see such divisions as 'flavesce-ns,' 'co-mmune,'

'macrant-hum' 'integrif-olia' and some others quite as startling.

If there

were signs up showing the families in a given lot, and if the labels gave the

common names and native home of some of the more important trees, even the professional

botanist would be pleased; to the ordinary visitor there would be added an

interest now quite lacking. The guide books give a bad English translation,

from the Dutch, of directions for seeing the garden. No one, however, unless

gifted with second sight, could even keep to the course mapped out, let alone

see the various objects mentioned. During my stay in Buitenzorg I used to get

out the guide book most religiously every Sunday. But although I spent some

hours every week day in systematic study of the gardens, I was never able to

follow with ease the official itinerary.

But even

if the guide book be maddening, one can find many interesting things without

great trouble. The Canary Avenue is something which never palls. The fine

collection of palms is a joy to look upon. There are all sorts of queer-looking

and strange plants to attract attention. Screw pines with their curious prop

roots interest every one and cycads and tree ferns deserve more than a passing

glance.

One

is sure to be impressed with the great number of trees bearing conspicuous

flowers. More than one man has asked me, on finding me to be a botanist,

whether our northern trees would blossom out handsomely if grown in the

tropics. Of course I have to say 'no'; that a leopard would more easily change

his spots.- It so happens that trees with large, showy flowers are more common

in the tropics than in our part of the world. But we have the catalpa and tulip

tree. There are plenty of trees in the tropics with inconspicuous flowers, too,

but these the non-botanist does not notice.

The climate of Buitenzorg is very moist, there being a yearly

rainfall of two hundred inches, or about six times that of New York. Dry spells

seldom last long and the atmosphere is nearly saturated with moisture at all

times. Correlated with the wet climate we find that many trees have leaves with

long pointed drip-tips. The water from the surface of the leaf collects on

these pointed tips and runs off quickly. Trees do not need a thick covering of

cork to protect them from drying out or to save them from cold. So we find,

instead of the thick, rough, furrowed bark of our own forests, only

smooth trunks even in the case of large and old trees. This often leads

strangers to underestimate the size of tropical trees, for they have come to

think of smooth bark as belonging only to small trees.

The limp, dangling leaves of some tropical

trees are most curious. They are frequently quite red, just as are the young

leaves of maples in temperate climates. It is not easy to say just why some

plants have adopted this peculiar habit of letting the leaves grow full size

before they are strong enough to stand out in proper fashion. Certain it is,

however, that. by hanging down in this way the young, tender leaves are much

less exposed, and hence in less danger of injury by excessive light and heat.

A moist climate, such as that of Buitenzorg, favors the growth of epiphytic or perched plants—also of parasites. Seeds or spores, carried by the wind or birds, find lodgment in the forks of trees. With plenty of moisture in the air and a constant warm temperature they grow luxuriantly. Thus it happens that trees are covered with moss. Even the very leaves are often marked with delicate patterns of moss and lichen. Orchids and ferns in great number are perched upon the horizontal branches and the smooth trunks also serve for the lodgment of many plants as well. Since Darwin's time every one has known something about orchids: plants with curious flowers adapted to insect visits—flowers of handsome colors and strange shapes. But many orchids have small greenish or white flowers, and these are the ones most common in the Buitenzorg garden. There is also a good collection of species which have been 'planted' not planted in the ground, but simply tied to tree trunks. Here they get along very well without drawing any water from the soil. There is plenty of moisture in the air and these plants are provided with absorbing tissues to take in what they need.

Things

grow on a large scale in the tropics. Many of our tiny herbs at home have

tropical relatives which are large trees. There are tree ferns, the tree-daisy

and the tree-tomato. In our own part of the world the sunflower is the largest

plant of the composite family, but in the tropics there are many shrubs and

trees belonging to this order of plants. Fruits of great size are common. A

good example is seen in the 'sausage tree' the fruits of which are great

sausage shaped structures two feet long, weighing many pounds. The jak tree has

a fruit which looks something like an enormous watermelon, except for the

roughened warty outer rind. The flowers, and hence the fruit, are on old

wood—not developed at the tips of young branches as are the apples, peaches and

other fruits familiar to us. Such production of flowers and fruits on the older

parts of the tree is known as 'cailiflorie' or 'caulanthy' the terms

meaning 'flower on the stem.' Caulanthy may often be seen in the tropics, while

among trees of temperate regions it is almost unknown.

Plants inhabited by ants are sure to strike the attention of

visitors. There are many of these so-called 'myrmecophilous'

plants in the garden at Buitenzorg; some brought in from the neighborhood,

while others, behaving like the fabled Topsy “just grew and grew.'” The

commonest are species of Myrmccodia, woody plants about two feet tall, with the

base of the stem much swollen and containing large winding passages swarming

with ants. These plants do not grow on the ground, but are attached to the branch of some tree, a

habit of life very common in moist climates. A handsome tree known as Humboldtia is

also myrmecophilous. The flowering

twigs are swollen and hollow—the cavity opening to the outer world by a small

hole through which ants enter. Apparently in these various cases the ants do

not serve the plants in any way. There are, however, certain species of Acacia, which

produce a sweet substance attractive to a certain kind of warlike ants, and

these ants protect the tree from the attacks of the leaf-cutting ants. Other

kinds of Acacia, not provided with ant police, are often

seriously damaged by the leaf-cutters.

In our

school geographies we have all read about the wonderful banyan tree which sends

down roots from its outspread branches and eventually covers a great area. A

whole avenue of such trees is to be seen at Buitenzorg. The trees are the 'waringen' a sort of banyan, and the

avenue is called the 'Waringen Alle.'

Other trees, such as the India rubber plant, have the same habit of putting

forth aerial roots which grow down and penetrate the soil and eventually cause

a wide spreading of the tree.

A

short magazine article cannot bring the reader very close to tropical plant

life as shown in the Buitenzorg garden, but the illustrations may help to make

clear some of the features I have mentioned. It must be understood that the

gardens are maintained primarily for scientific purposes and that there are

countless objects, interesting to the botanist, the enumeration of which would

be wearisome to the general reader.

It is the

wish of the director of the gardens that botanists from all countries should

make use of the garden for study. At his suggestion the government erected some

years ago a commodious laboratory for the exclusive use of visiting men of

science. Naturally enough, since Java is a Dutch dependency, most of the

visitors thus far have come from Holland, but many Germans have also been

there. Almost no Americans have studied in Buitenzorg. This is the more

strange, since our botanists are accustomed to travel long distances and many

have worked in Europe. With the increased importance of the tropics which has

come in recent years, there should be a greater interest developed in the study

of tropical life. It is much to be desired that our own botanists make use of

this and other tropical gardens in order that we may not remain behind other

nations in this important branch of natural science.

Popular Science Monthly/Volume 67/November 1905

The Botanical Garden at Buitenzorg, Java

*************************************************************

Album XV * Image 25 * Size 11 x 8 inches

The actual location is Jaipur (Jeypoor) India.

Upper right the façade of the Hawa Mahal (Palace of the Winds) built of pink granite in

the form of a high wall to screen the royal ladies as they watched street festivities.

MANACK CHOUK

Album XV * Image 25 * Detail from full size 11 x 8 inches

The actual location is Jaipur (Jeypoor) India.

and the main square Manack Chouk, also known as Ruby Square.

MANACK CHOUK

Album XV * Image 25 * Detail from full size 11 x 8 inches

The actual location is Jaipur (Jeypoor) India.

These two photographs have been added to BLOG 50 - WORLD TOUR - ARTICLE 9 of 28

******** ******** ******** ******** ******** ******** ******** ********

>+< >+< >+< >+< >+< >+< >+<>+< >+< >+< >+< >+<

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61551067101475

No comments:

Post a Comment